‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ was the question that Reg asks the restless crowd in Monty Python’s ‘Life of Brian’

Of course, numerous examples of what they had done were offered in response! Discoveries of Roman artefacts around the vicinity of Southwark Cathedral and in the Borough over the last few decades and more recently have helped us to build up a more complete and fascinating picture of ‘Roman Southwark’. This was a community in its own right, with its bath houses and villas and places of worship and remembrance. The display in the Cathedral of artefacts unearthed over the last 40 years give us a glimpse into that world but also introduces us to some of our predecessors in the area, our neighbours, long gone but now, not forgotten.

Matrona, maybe a woman from North Africa; Cassianus, who set up an altar – who were these people and what was their story? A panoply of gods being worshipped – Neptune, Apollos, Mithras – devotions brought to our area from across the known world, until another faith arrived from an eastern outpost of the Roman Empire that would eclipse them all – Christianity.

What this online exhibition reveals is the sophistication, diversity and faithfulness of the area, part of our story, part of what continues to make the area what it is, not just history but a glimpse into life.

Introduction

Over 1500 years ago a set of Roman objects was placed into a well near to this site. They were not seen again until 1977, when they were found by archaeologists excavating in the Cathedral. The group of objects on show here were taken to the Cuming Museum on the Walworth Road and went on display until 2000.

For the past 17 years they have been in the Cuming museum’s stores. Southwark Cathedral and the Cuming museum are delighted to put these beautiful objects on show again for this website.

Romans in Southwark

All these artefacts are from a time when Romans still occupied large parts of Britain. The Romans, under Emperor Claudius, invaded Britain in AD43.

Around seven years later they created what we know today as Londinium, on the north shores of the marshy Thames. It would have roughly been where the City of London is today. They had had to begin their settlement of the north side by camping in and crossing from the south and this encampment grew into a major settlement in its own right, now known as Southwark.

Southwark was the place where the main Roman roads, which ran from Londinium to the southern coasts, met before the crossing the river into Londinium itself. Roman Southwark included a port, many fine buildings, lots of trades and industries, wealthy homes, burial sites and possibly places of worship.

The Roman Empire ruled Britain for the next 400 years but broke apart in the 5th century. These islands were Rome’s furthest Western outpost and very hard to keep going in troubled times. So Britain was largely abandoned. Britain began to lose much of its Roman side and its Roman buildings and traditions began to fade.

Our Roman forebears brought all their practices and beliefs with them and left us clues to their attitudes to death, burial and “spiritual” life. But local Britons and their Roman occupiers mixed together and so both gods and practices often became blended together. Many of these artefacts on show here have influences from the local area, the Romans and other parts of the Empire.

Excavations beneath the Choir of Southwark Cathedral, 1977

Southwark Cathedral sits on land that was once part of Roman Southwark. Many Roman items have been unearthed during the last few centuries during repair and building work on the Cathedral site and in the surrounding area. In 1977 a sealed crypt below the Choir was reopened so that it could be cleared and its contents reburied elsewhere. The Cathedral invited the Southwark & Lambeth Archaeological Evacuation Committee to carry out the work.

The crypt, constructed in 1703 and sealed in the 1840s, already contained a number of 18th and 19th century coffins. When these were removed, the archaeologists discovered that the construction of the crypt in the early 18th century had wiped out many layers of archaeology. However around half a metre of the site clearly dated from the second half of the first century A.D. In this section they found a well and it was in this well that the sculptures and carved stonework were discovered. These items were found amongst other debris dating to the Roman period. In fact the whole well was full of Roman material suggesting that it had been deliberately filled in during the time of the Roman settlement, possibly the 4th century AD.

It is thought that the items might have been deposited down the well when the rise of Christianity meant non-Christian gods were rejected, sometimes forcibly. There is sign of charring on a couple of pieces, hinting that perhaps there might have been some burning of the objects. But these items have as much or more to do with burial rituals than worship so there need not have been any reason to particularly damage them. Research is continuing into these and other similar finds.

The Objects

Altar

This Altar piece is inscribed "...CASSIANUS/POSVIT..." (“... Cassianus…set up…). So very likely that is the family name of the person who set up the altar. It may originally have been at the base of a carved figure. It is made of limestone, which is a soft stone, and as a result this material has become even more worn away after burial.

Tombstone

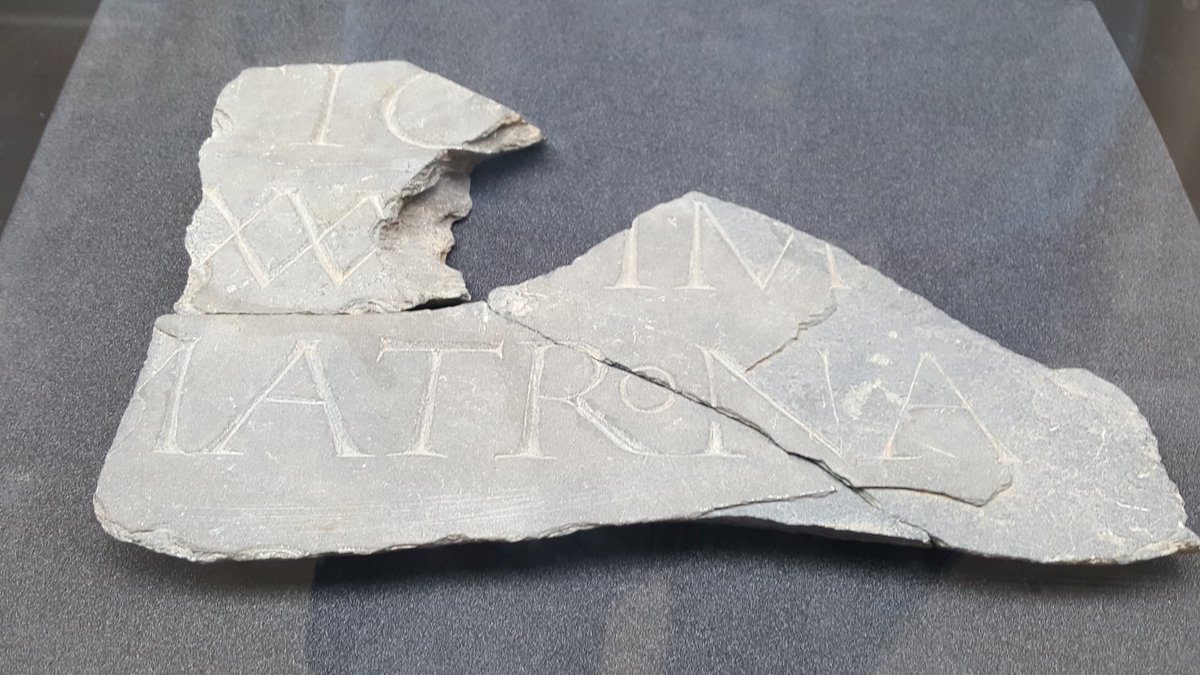

This tombstone was found at a slightly higher level in the well than the rest of the pieces so it could have been deposited quite a bit later. inscribed with part of a name (…TIC or …TIO), four numerals of the age of the deceased (and the name "MATRONA", the name of the woman who dedicated the stone. The three Xs and the I after a gap for another numeral mean the person was most likely to be in their mid thirties, possibly 36. The name fragment is thought to be that of a man. “Matrona” seems as if it could be something to do with the relationship to the deceased but in fact Matrona was also a common woman’s name throughout the Empire, particularly from someone from North Africa.

Genius

Statue of a “Genius”, a minor god which could act as a personal deity or kind of “guardian angel” for a person or household or a place. The figure wears a toga and carries a “cornucopia”, or basket of plenty. It once stood on an altar, over which it was posed pouring an offering. The altar, head, arms and legs are missing. He is made of sandstone but it hasn’t been identified where the stone might be from and so this makes the piece harder to date and place. Perhaps it was locally made. The sculpture’s form is a quite standard Greek-Roman format but it is decorated with lots of native British influences, so the maker followed the Empire tradition for the form but also blended in local patterns and symbols.

Cinerary Chest

Cover for a Roman funerary ash holder for holding human ash remains. A sculpted female figure reclines on the top, on a couch, holding a bunch of grapes in her right hand. It was described as a “lid” for a funeral chest but it does not appear very secure as a lid. It possibly sat over the top of a chest for holding ashes but might also have simply covered a hollow for the ashes which would be built into an alcove. This kind of sculpture is familiar in Etruscan funerary art, but unique in Britain

and rare elsewhere in the Roman world. It could date from around the third century AD, at a time when the Roman custom of cremation was losing favour and burial was becoming more popular.

Figure

Part of a classical figure sculpture, possibly of a sea god, such as Neptune or Oceanus, with a dolphin. Only the left leg and the dolphin remain. It is made of marble from the Greek islands and it dates from the first or second century AD, making it the oldest of the well sculptures here. It was already an antique when it was destroyed and imported as a finished work of art. It could have been a temple offering but it is more likely it was a prized object decorating a wealthy private household.

Hunter God

This piece is a copy and the original is still in the Cuming museum. The stocky figure with cap, quiver, cloak, sandals, short tunic and short sword is thought to be a male god of hunting. He is the largest of the group and is the most complete, so he makes an impressive sight. A figure of a dog and a deer are at either side, with the dog looking devotedly up as his master. When the sculpture was discovered in the well, it was in three pieces; he was broken across the middle and the top of the arrow heads was also separated from the main pieces.

It has been very difficult to decide who “he” is supposed to represent, if anyone. The two animals are most closely associated with the goddess Diana, as is the pose the figure is making. However the hunting associations and male aspect might point to her close male version, Apollo. Or the cap might point to the god Mithras. There was a Mithras cult over the water in Londinium and it would have been surprising if it had not travelled over to Southwark. Other suggestions or references might include deities such as Silvanus, Maponus, Cunomagolus, Attis or Cybele.

It seems that a local sculptor was attempting to create a three-dimensional sculpture with a nod to classical style but with his own flavour added.

The Cuming Museum

These objects on are from the Cuming museum, which has a worldwide collection, a London collection and a Southwark local collection. The original museum was opened in 1906 and was formed from the collections of father and son Richard Cuming and his son Henry Syer Cuming. Between them these men wanted to create a British Museum in miniature and their house on the Walworth Road was filled with nearly 100,000 objects. Henry continued his father’s collecting and when he died in 1902 he left the collection to the parish of St Mary Newington with funds to build a museum gallery.

This was done, opening in 1906 in a gallery on the first floor of Newington public library before moving next door to the former Walworth Town Hall in 2006. Generations of Southwark people visited the museum and its temporary exhibitions and schools enjoyed the facilities and museum education activities. However in 2013 the former town hall building suffered a major fire. Although the collections were largely saved the museum galleries were extremely badly damaged.

The museum collection is safe in storage and is loaned out to other museums and organisations, such as Southwark Cathedral, along with education programmes and activities.

The museum has over 30,000 objects and these are being digitised and put online. You can see a selection of them if you visit the collections website. We welcome enquiries and hope you will enjoy this online exhibition.

Email us: cuming.museum@southwark.gov.uk

Browse the collections: https://heritage.southwark.gov.uk

Follow us on Twitter: @SwkHeritage